Introduction

This brief reflection describes the historical and contemporary conditions of the United States’ and Mexico’s labor markets; it raises the need to recognize, legalize, and order the real and effective integration of those markets and proposes a critical route to achieve it. This integrative solution involves the trade relationship, specifically the United States-Mexico-Canada Treaty (USMCA). However, it is argued that the effectiveness of this resource will depend on the political will of the parties to expand or modify the use of USMCA’s Chapter 16 for greater and better organization of labor markets for the benefit of both countries and, potentially, for Canada as well.

United States’ and Mexico’s labor markets, and their interaction

The labor markets of the United States and Mexico have maintained a historical interdependence based on two factors. The first is American economic vitality, which requires a constant supply of labor, and the second is Mexican demographics, which has generated a constant surplus of labor throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, although there are some expectations that demographic changes in Mexico in the coming decades will modify this condition. This context has generated structural complementarity in both labor markets, which has manifested itself in a constant migration of Mexican citizens to the United States.

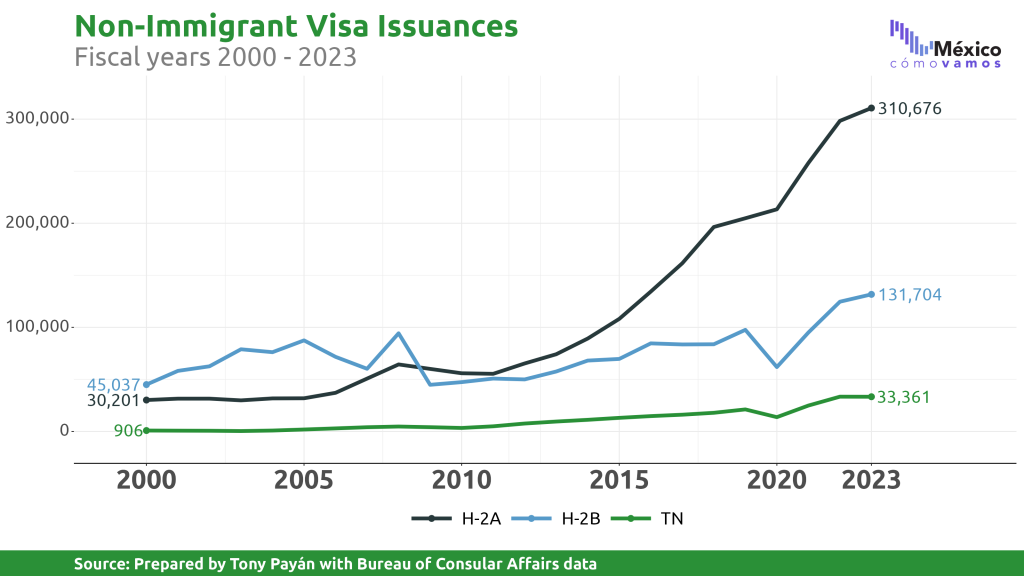

Despite this historical and structural complementarity, labor integration between both countries has occurred erratically and has followed two different routes. One of them is the legal route that, in addition to 5.4 million authorized permanent residents and naturalized citizens born in Mexico, is made up of a variety of worker programs with employment visas, including H1-B visas for professionals, H2-A for agricultural workers, H2-B for non-agricultural workers, and the TN visa, also for professionals. This last category of visa was initially contemplated in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and is currently regulated by USMCA. The second route has involved a constant flow of undocumented migration of Mexicans to the United States, which has resulted in the presence of at least 5.3 million workers born in Mexico, but without permission to work in the United States.

This presence of millions of documented and undocumented Mexican workers in the United States speaks for itself of the need for an integrative, legal and orderly solution to the labor markets between both countries.

The conditions of the labor market in the US

The strength of the US economy in the post-COVID-19 period has required greater quantity and quality of workers. In the first quarter of 2024, the United States economy had 8.1 million vacancies and only 6.1 million unemployed, that is, a deficit of 2 million workers. This deficit, which can become a structural problem in American labor markets, can only be covered by the addition of more workers, either by native population growth or by an increase in immigration. Neither of these routes is sufficient. The population growth rate in the US continues to slow, due to a drop in fertility rates, one million deaths from the pandemic, and the acceleration in retirement rates of the generation known as boomers. On the other hand, migratory routes remain structurally limited. The worker visa system is limited and has features that limit people’s chances of entering the US labor market, including high costs and complicated paperwork.

Mexico emigrates again

The need for labor in the US labor markets is accompanied by several conditions that are beginning to encourage migration from Mexico, after having been on the decline for several years. The main conditions are the suboptimal performance of the Mexican economy in recent years, with an average growth of just 0.8% in the last six years. This low growth is driving a new exodus of workers to the United States—approximately 48,000 Mexicans have been detained at the border monthly from 2021 to 2024. Social programs, mostly cash transfers, have not had a deterrent effect among many Mexicans who prefer to work in the United States. Furthermore, growing public insecurity is spurring the exodus of middle- and upper-class Mexican citizens, with large numbers moving their capital, their families, and their businesses to the United States—many of them on temporary or investment visas. This indicates that, in the immediate future, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans will continue looking for work and investment opportunities in that country.

The USMCA and the labor chapter: a special visa

The conditions of the United States economy—with a constant demand for workers—and the economic and security conditions in Mexico that encourage a new exodus are a set of factors that urge governments to order and regulate labor markets to avoid irregularity and benefit both countries. The critical path to achieve this is found in the USMCA, specifically in its Chapter 16.

Now, USMCA, formerly NAFTA, is not explicitly a labor treaty. However, it contains a section inserted based on a request from the Mexican government in the early 1990s. The treaty says:

Article 16.4: Authorization of Temporary Entry 1. Each Party shall authorize temporary entry to a business person who is qualified to enter in accordance with its measures related to public health and safety and national security, in accordance with this Chapter, including the Annex. 16-A (Temporary Entry for Business Persons).

For the purposes of its implementation, the United States created the TN visa, with which Mexican and Canadian citizens can access the US labor market, if the applicant’s profession is on the list of professions listed in the annex. The effect has been an increasing, although still limited, use of this visa, as the graph shows. What limits the use of this visa is mainly the limit imposed by the list of 63 professions, which are already out of date with the 21st century’s third decade’s labor reality. What makes the use of this visa easier is that, unlike other visas, its cost is relatively low, it has no numerical limits, it is renewable indefinitely, and, above all, it is a flexible labor integration instrument because it is de facto indexed to the economic performance of the United States. When the economy grows, job offers are generated in greater numbers and therefore there are greater requests for visas. When the economy slows down, job offers decrease and therefore there are fewer visa applications. In this sense, it is the labor market that determines how many visas are requested and granted annually.

The visa, however, has the important limitation that only 63 professions can access it, in a labor market where categories of existing professions number in the tens of thousands and the existing professions of the 21st century’s economy have changed substantially after more than 30 years of the list’s elaboration. Consequently, many professionals access this visa under the category of “consultant,” in part because their professions do not find a place in the list of the annex, which distorts the original intention of this visa.

All of this points to the need to update USMCA’s Chapter 16, which was transferred without changes in the renegotiation of NAFTA, now USMCA, between 2017 and 2020. The opportunity to do so is presented in the mandated review of the treaty by the same agreement in Chapter 34, Section 7, for the year 2026. There are, however, important doubts regarding the reopening of the treaty, due to the political environment that prevails in both the United States and Mexico. These doubts also exist in Canada, although that country has been more proactive and is already preparing several scenarios for the defense of the treaty in case it were to enter a renegotiation stage. Experts have suggested leaving the treaty unchanged and reducing the risk of substantive modifications or even cancellation if a new renegotiation is opened. Given this fear, there is another way to modify Chapter 16, without the need for renegotiation.On October 7, 2003, there was a decision regarding NAFTA, precisely on Chapter 16. In this decision the NAFTA Commission expanded the definition of the profession “Mathematician” to include the profession of “Actuary.” Likewise, the term “Biologist” was expanded to include the profession “Plant Pathologist.” The NAFTA Temporary Entry Working Group (TEWG) accepted this decision, which went into effect on February 1, 2004. The TEWG also requested to develop trilaterally agreed upon procedures for adding and removing professions from Appendix 1603.D. 1 (Professionals) of NAFTA. The three countries accepted this agreement based on the facilitation of cross-border trade in services. The Temporary Entry Working Group is led by Canada, but this proposal can be presented to the United States Trade Representative (USTR) with the coordination of Mexico and Canada and, preferably, in coordination with the private sectors of the three countries. This solution is convenient because it would not require renegotiation of the treaty.

Labor markets and the review of the treaty in 2026

In preparation for the review of the treaty in 2026, the Canadian government has already begun its work. The House of Commons ordered its first study on the issue, and included representatives from industry, trade associations, unions, civil society organizations and research centers. Ottawa hopes to formulate its position on the treaty revisions in 2025. Mexico, for its part, has begun some preparatory work for the 2026 revisions. These deliberations should include an expansion of the list of professions eligible for the TN work visa or even requesting that this be a negative list—specifying the professions that do not qualify and letting the labor market determine workforce integration in North America. However, if the preference is for the treaty to be revised in relation to its operation, but not open to renegotiation, the Government of Mexico must propose these modifications through the trilateral commission that made the changes to the list in 2003.

Conclusion

Given the impossibility of a comprehensive immigration reform in the United States and the evident and unstoppable integration of the labor markets of both countries, it would be a mistake not to explore such a promising route to take advantage of the complementarity of these two economies in labor markets in a legal and ordered manner. The USMCA offers a clear and relatively effective path, even though either path—a complete opening to renegotiation of the treaty or a change to the list of professions through the trilateral work of the TEWG—involves significant risks. The alternative is the status quo —unauthorized, documented, multi-route labor integration, with inefficiencies in labor markets and irregular migration that constantly irritates the binational relationship.

References:

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024, June 4). The Employment Situation. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

Cornelius, W. (1998). The Structural Embeddedness of Demand for Mexican Immigrant Labor: New Evidence from California. In Suárez-Orozco, M (Ed.), Crossings: Mexican Immigration in Interdisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 113-155). Harvard University Press.

Migration Policy Institute. (2019). Profile of Unauthorized Population: United States. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/US#topcountries

Statistica. (Marzo, 22). Montly Job Openings in the United States from March 2022 to March 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/217943/monthly-job-openings-in-the-united-states/.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. (2024). Nationwide Encounters. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/nationwide-encounters. USMCA’s Free Trade Commission. (2003). Celebrating a decade of USMCA. http://www.sice.oas.org/tpd/nafta/Commission/2003meeting_s.pdf.

Click on the postcard below to go to the site.