Competitiveness and the future of North America depend, among other factors, on capitalizing on the region’s talent. Unlike the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) includes provisions that consider the labor aspects of productive integration to strengthen the region’s competitiveness and its population welfare. However, unlike other integration schemes such as the European Union or the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), the USMCA does not consider a North American labor market integration path, nor the free movement of workers within the free trade zone, which could be a barrier to reaching the region’s productive potential.

How does the USMCA consider the labor integration component?

While the USMCA aims to foster regional competitiveness, Chapter 26 on competitiveness is merely a cooperation framework. It includes provisions for establishing a Competitiveness Committee to develop “cooperation activities” to “improve the competitiveness of North American exports” (Art. 26. 1. 2. and 4.). This chapter states that the Committee must develop a work plan, but does not mention talent as a factor for increasing regional competitiveness. It invites working with “other committees [and] working groups” under the Agreement (Art. 26. 1. 8.), opening the door to the possibility of promoting collaboration on temporary business person entry to enhance regional competitiveness. The Competitiveness Committee could even become “a forum for the three governments to discuss workforce development challenges.”

Unlike NAFTA, which handled labor aspects through the Labor Cooperation Agreement, the USMCA integrated Chapter 23 on labor into its text and subjected its compliance to the Dispute Settlement Mechanisms in Chapter 31. The partners committed to observing Labor Rights established in the International Labour Organization (ILO) Declaration related to trade and investment (Art. 23. 3.). It also aimed to ensure respect for workers’ rights established in national laws. Each Party will adopt and maintain laws and regulations overseeing minimum wages, working hours, and workplace safety and health. However, this chapter does not furnish the free movement of workers nor the integration of the region’s labor markets.

Chapter 23 is complemented by two Rapid Response Labor Mechanisms (RRM) in Specific Facilities: one, for Mexico-United States (Annex 31-A), and the second, for Mexico-Canada (Annex 31-B). They focus on ensuring the protection of workers’ rights, particularly in Mexico, without opening any pathway for labor mobility in the region. The RRMs were installed to “guarantee the remediation of a Denial of Rights” of workers regarding freedom of association and their right to collective negotiation.

Chapter 16 is the third chapter in the USMCA that includes regional rules for people’s mobility. Chapter 16 on Temporary Entry for Business Persons includes provisions negotiated in NAFTA in the early 1990s to facilitate the free movement of service providers. With the renegotiation of NAFTA, Chapter 16 was transferred, unchanged, into the USMCA. It remained as Chapter number 16.

In this chapter, rules to allow cross-border trade in services between USMCA partners’ markets through Mode 4 of service delivery are established. Specifically, it allows for temporary entry for Business Visitors from any of the three countries, without requiring employment authorization. The activities a Business Visitor is authorized to perform are defined in Appendix 1. It also provides temporary entry for three other categories: traders and investors, intra-company transferees, and professionals. For professionals, it allows market access to “a business person seeking to engage in a business activity at a professional level in a profession listed in Appendix 2,” which includes 63 types of professions such as agronomist, economist, mathematician, nutritionist, or university professor, among others. It establishes the minimum academic requirements and alternative titles that must be presented. Mexican professionals wishing to access the US market, and whose professions are included in Appendix 2, can apply for a visa founded under the Agreement known as the TN visa, which does not impose quantitative restrictions, nor limits on the years it can be retained. In the case of the Canadian market, for a Mexican citizen to offer professional services, a Labor Market Impact Assessment is not required, and they must demonstrate qualifications to work in one of the 63 applicable professions, either through a degree or certification, as well as evidence of a job offer from a Canadian employer.

Chapter 16’s provisions do not seek to facilitate access to another Party’s labor market, nor do they apply to citizenship, nationality, residence, or permanent employment measures. The USMCA does not foresee North America’s workers’ free movement across its borders, nor does it propose creating an integrated regional labor market. The provisions only refer to temporary (non-immigrant) entry and require any Mexican citizen intending to do so to obtain a visa to enter the United States or Canada.

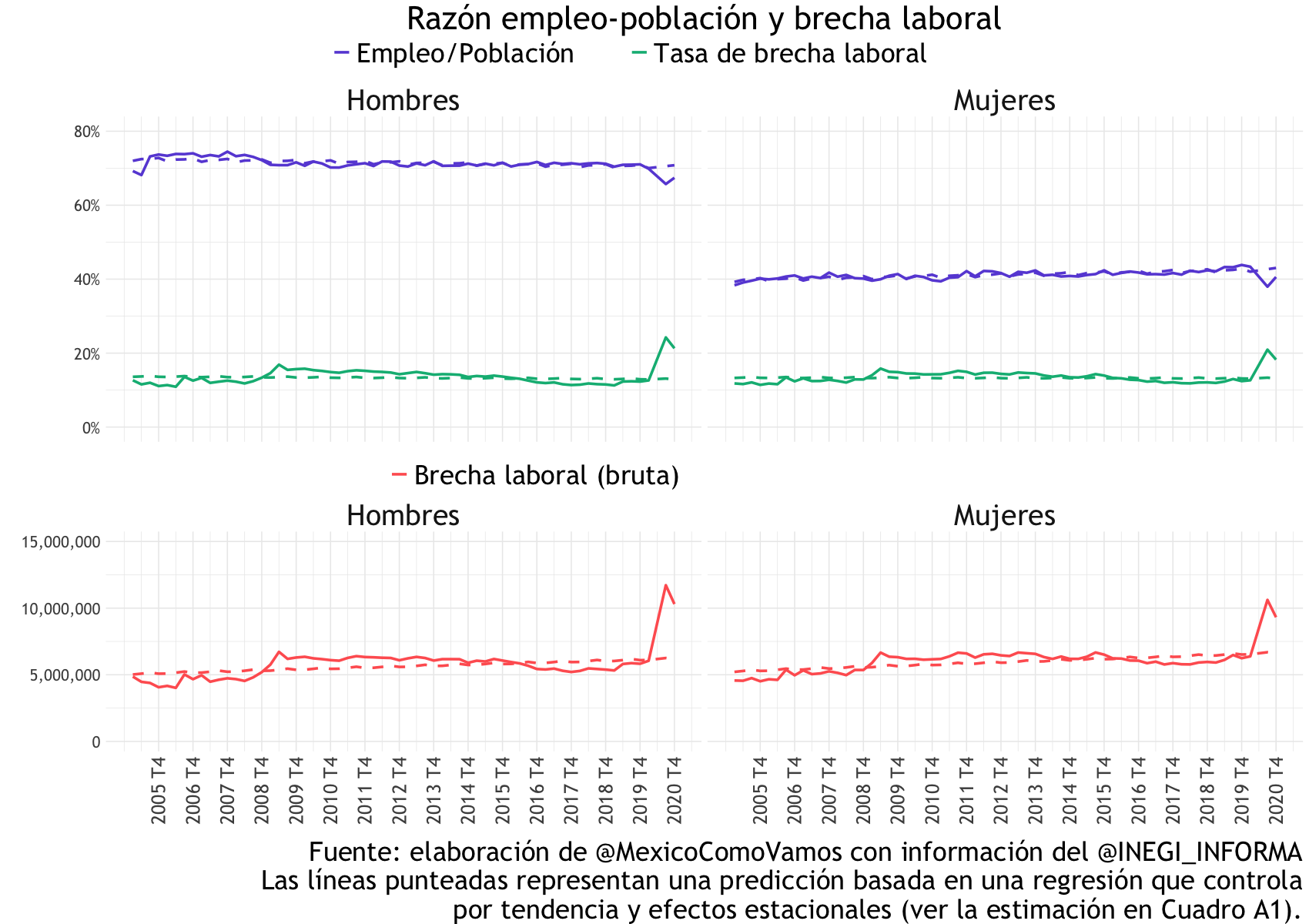

The labor market in North America shows a shortage of talent in terms of quantity and quality to meet the needs of the productive sector. For example, of the 12 million workers in the manufacturing sector in the United States, about 53% are over 55 years old. This means that, in the coming years, the country will require personnel to fill these positions and likely many others in other sectors to keep up with the development of its economy.

Significant challenges are expected to meet the region’s labor needs in the coming years. These challenges include global competition for talent, the automation of certain activities, and the need to adapt to new technologies and work modalities. To address challenges that affect the region, the solution also requires a regional perspective.

In 2026, the first review of the USMCA will take place. Although this Agreement does not seem to be the legal framework from which a North American labor mobility agenda can be defined, its implementation has stressed the urgent need for specialized professionals and technicians, to ensure the region’s dynamism and competitiveness. North America urgently needs to develop schemes that allow some form of worker mobility to meet the existing demand. This would amplify the region’s productive activity and growth, especially given the relocation of companies to the region due to the trade war between the United States and China, as well as other current geopolitical factors.

A more fluid labor market would allow companies to adapt more quickly to changes in demand, market trends, and technological advances, positively impacting their responsiveness and competitiveness against third parties, particularly Asian ones.

Labor mobility in North America has the potential to be a fundamental driver of increasing regional competitiveness. Leveraging labor mobility strategically, equitably, and sustainably will be crucial to propelling the region’s economic growth, innovation, and human development, whether within USMCA’s framework or outside of it.

La movilidad laboral en América del Norte tiene el potencial de ser un motor clave para elevar la competitividad regional. Será fundamental aprovechar la movilidad laboral de manera estratégica, equitativa y sostenible para impulsar el crecimiento económico, la innovación y el desarrollo humano en la región, ya sea en el marco del T-MEC o fuera de éste..

Click on the postcard below to go to the site.