In 2024, the wave of presidential elections worldwide brought significant shifts, including Mexico’s historic election of a woman as president for the first time. Meanwhile, with the victory of Republican candidate Donald Trump in the United States, Mexico now faces potential challenges posed by his policy agenda on the countries’ trade relations. Moving forward, North America’s three nations must work together to build a cohesive strategy as they approach the first review of the USMCA, where challenges that transcend borders remain.

North America has a historic opportunity to harness the region’s potential by leveraging its complementarity in trade and the talent of its human capital. Setting shared goals for the future is the only way to ensure that we continue to build upon our success story.

Integration through the USMCA

The USMCA is North America’s greatest comparative advantage

The process of North American trade and economic integration, initiated 30 years ago with the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, has witnessed systemic changes worldwide. Building on accumulated experience in areas like trade and investment, the USMCA came into effect in 2020 as NAFTA’s successor, with its first review scheduled for 2026. This will offer the three member countries an opportunity to assess whether the treaty’s goals and benefits have been realized.

Just as NAFTA faced systemic changes, the USMCA and its upcoming review will unfold in a context of political shifts, including presidential elections in Mexico and the United States, U.S.-China tensions, armed conflicts, and the pandemic’s impact on global supply chains. The resilience of the USMCA is stronger than the sum of its parts, meaning that North America’s continued success story will depend on its members maximizing the potential of this unique agreement.

The USMCA allows flexibility for its members to express concerns or propose adjustments through negotiations, but these must align the demands of sovereign nations with the benefit of the region as a whole. A relevant example was the U.S.-China trade tensions that led Mexico and Canada to reconsider their positions with the Asian power. Within the framework of the agreement, the U.S. implemented strict rules of origin to limit Chinese products and investments, decisions not always aligned with Mexico’s best interests.

By 2026, North America must deepen the integration of its supply chains to make them more resilient and increase the regional value of production. Achieving this goal is only possible through a shared commitment to coordinated measures; otherwise, it will be more challenging to prevent each country from acting solely in its own interest, potentially compromising the rest of the region.

Similarly, the dispute resolution mechanism (Chapter 31) serves the purpose of allowing treaty members to voice their concerns. In cases where a ruling is reached, a Final Report is issued. By 2026, compliance with panel rulings and the commitment to resolve outstanding disputes will be essential to prevent tensions from escalating into a more significant issue.

An integration beyond economics

The close relationship between Mexico and the United States goes beyond being primary trade partners; it suggests a socio-economic convergence, especially visible in the southern U.S. and northern Mexican states, where common challenges and shared lessons in areas like education and healthcare drive social progress.

North America’s success story presents an opportunity to reverse the setbacks in the southern-southeastern region of Mexico and promote advancements in social progress. The goal is to create conditions that attract new investments, which, in turn, will strengthen the labor market and improve people’s quality of life.

Nearshoring: resilience of supply chains in North America

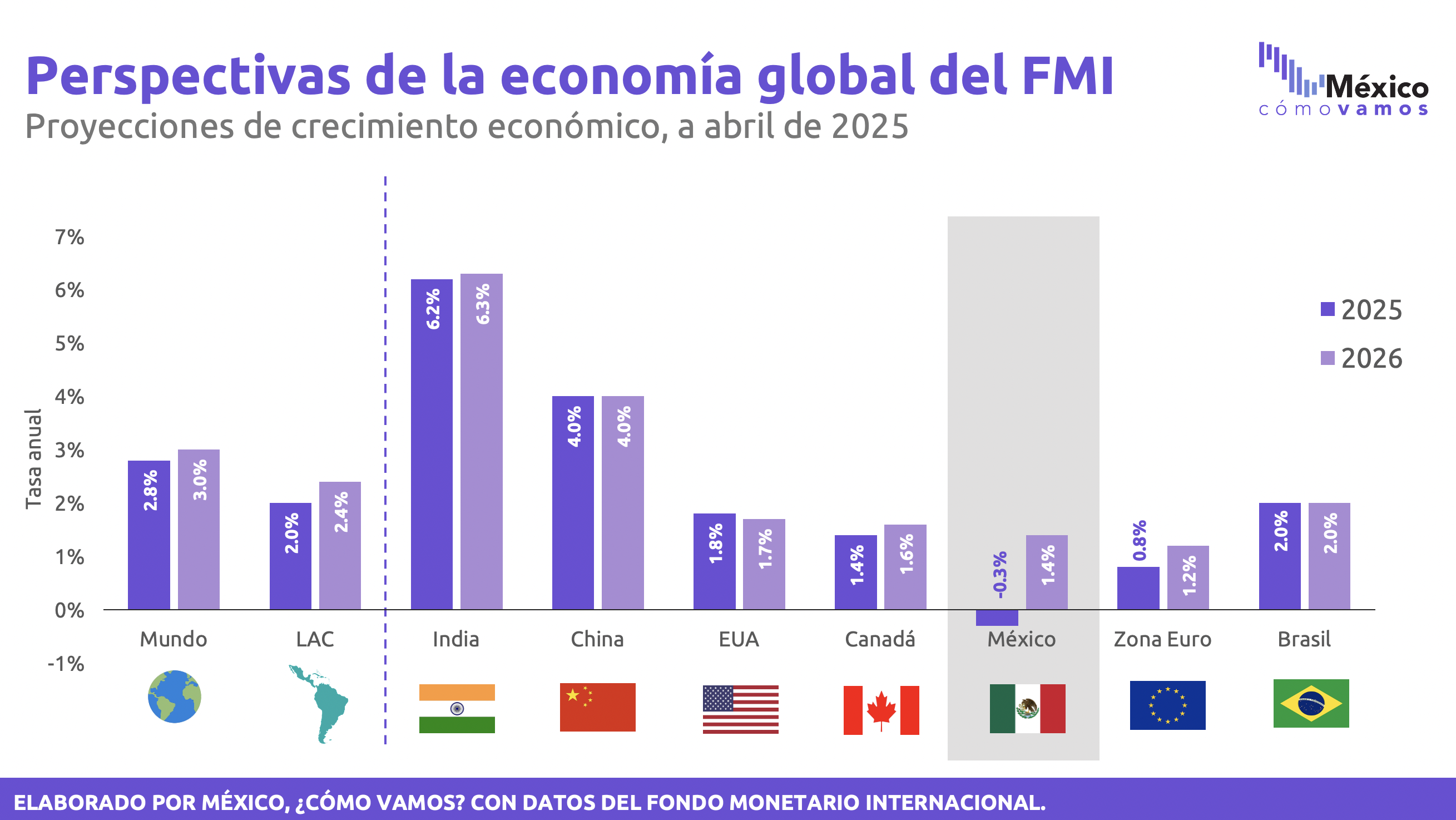

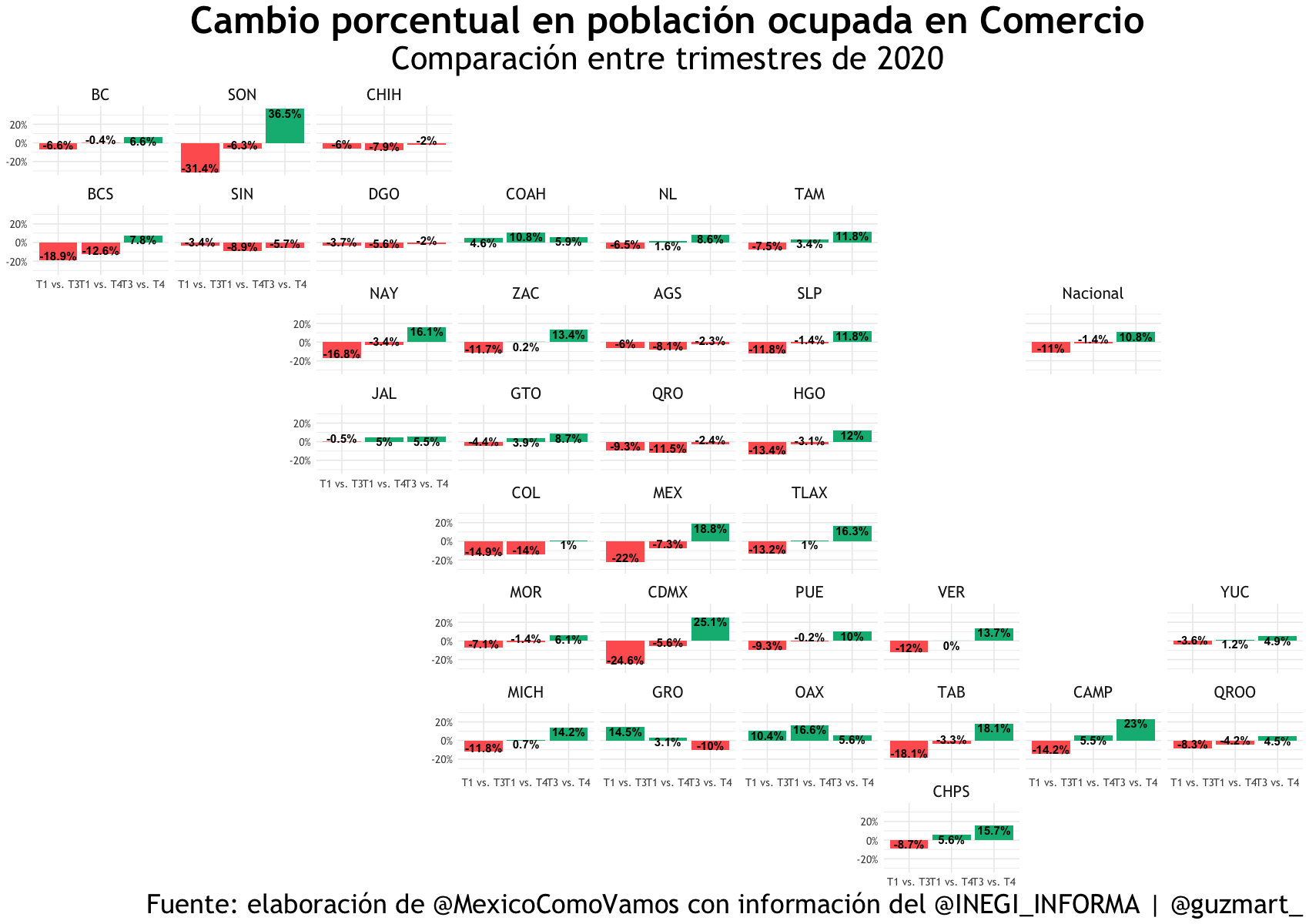

The pandemic disrupted supply chains for goods and merchandise worldwide. In North America, actions taken against China accelerated a phase of relocating production closer to the end consumer, giving rise to a new supply chain strategy known as nearshoring. The most evident indicators of relocation effects in Mexico have been in investment and high demand for industrial parks. However, this phenomenon has yet to be reflected more intensely in Mexico’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

- 44% of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) that Mexico receives comes from the United States, and 8% from Canada (as of Q2 2024).

- Mark Thomas, the World Bank representative for Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela, estimates that the impact of nearshoring on the Mexican economy has been 0.2% of GDP.

Secondary activities, such as the manufacturing sector, have been the main beneficiaries of nearshoring in terms of both investments and job creation.

- 36% of FDI from the United States is directed toward the manufacturing sector, which holds the largest weight in the Mexican economy (as of Q2 2024).

- 43% of Canada’s FDI in Mexico targets the transportation, postal services, and storage sector, which represents 7.93% of Mexico’s economy (as of Q2 2024).

- The productive sectors tied to the trade of manufactured goods (wholesale trade, transportation and storage, manufacturing, and financial and insurance services) currently account for 56.5 million jobs across the region.

As we approach the 2026 review, the North American automotive industry’s success story should serve as a model for resilient and integrated supply chains.

- The automotive industry is the largest component of total trade in North America, representing 22% of USMCA trade.

- Two of the top three goods traded between Mexico and Canada are the same in both directions: passenger vehicles and vehicle accessories.

- The automotive supply chain creates jobs across Canada, the U.S., and Mexico, representing 20% of FDI, 4.7% of national GDP, and 23% of manufacturing GDP (AMIA, 2023).

- 32% of Mexico’s manufacturing exports correspond to the automotive industry (AMIA, 2023).

- The industry is a top generator of foreign currency, with a surplus in the automotive trade balance.

While the benefits of nearshoring are evident, they are not evenly distributed across all regions of the country due to factors like the economic lag in the south-southeast, insecurity, and lack of legal certainty for new investments in the automotive sector. To avoid bottlenecks in the coming years, Mexico’s domestic policy must focus efforts on strategic sectors like automotive, leveraging the country’s economic strengths to bring dynamism to all states, as investment primarily flows to those with a high degree of social progress.

Labor mobility

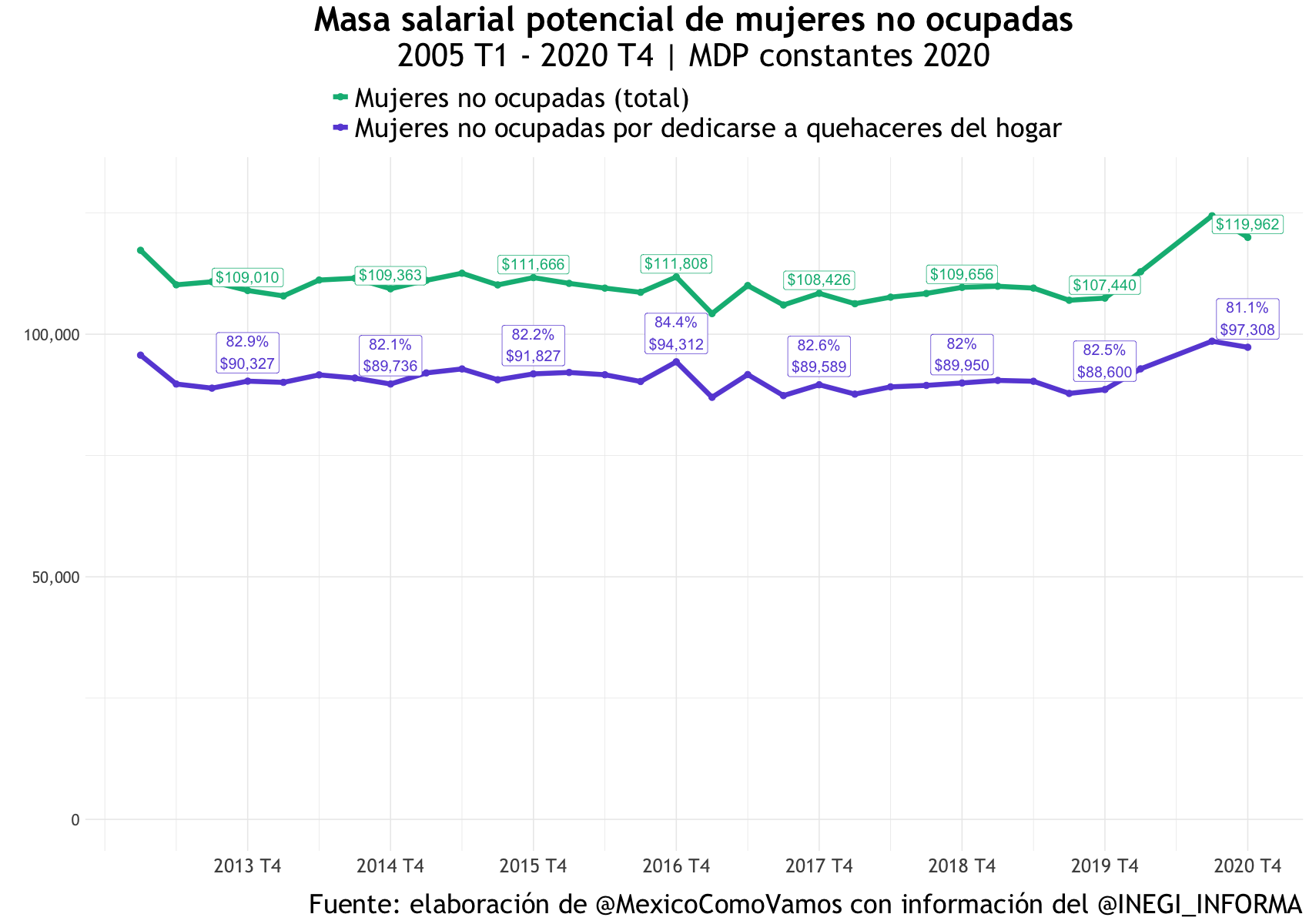

The USMCA modernized trade in North America, but some chapters retained from NAFTA make it difficult to adapt to new challenges and demands, such as Annex 16-A of Chapter 16 in the USMCA. The North American labor market now requires new skills in professionals due to nearshoring, and given that immigration policy is a sensitive point in our relationship with the U.S., we are underutilizing tools within the USMCA that could address these needs.

Chapter 16 of the USMCA, which covers the temporary entry of business persons, is a unique advantage for Mexicans and Canadians as it provides preferential access for professionals from these countries who seek to work in the U.S. The main issue is that the list of professions has not been updated since 1994. Modernizing the list of professions is a key recommendation for achieving orderly and legal labor integration. This update would also benefit the U.S., which faces an aging population and millions of job vacancies.

The demand for new skills and professions driven by nearshoring can be met through NAFTA – visas established under Chapter 16. However, updating the list of professions to reflect future needs remains a challenge as we approach 2026. Among the occupations with the highest growth in nearshoring-related hires are sectors like construction and engineering, which saw double-digit growth between 2022 and 2023.

Challenges towards 2026

Rule of law

The recent approval of the judicial reform in Mexico has generated uncertainty for the financial market, international media, human rights organizations, and chambers of commerce. As one of the world’s largest economies, Mexico’s strong rule of law is a symbol that common rules are respected and that conflict resolution mechanisms are in place, which is essential for investors and trade partners.

- México, ¿cómo vamos? stated, ‘The reform contradicts the USMCA in areas of trade integration (chapters 2, 18, 21, and 22) and labor (chapter 23). It also opens the door for special interest groups to influence justice in Mexico, compromising human rights and quality of life.’

- Ken Salazar commented, ‘I believe faith and trust in the rule of law are among the shared values that unite our nations, while for the private sector, they establish a foundation for building confidence and fostering investment in a stable and predictable environment.’

- Michael Stott for the Financial Times noted, ‘Few would argue that Mexico’s judicial system doesn’t need improvement. Many crimes go unpunished, and corruption is a significant issue. But business leaders fear that López Obrador’s changes will worsen the situation by politicizing justice.’

- Morgan Stanley remarked, ‘We believe replacing the judicial system could increase Mexico’s risk premiums and limit capital investment. That is problematic, as nearshoring is reaching critical bottlenecks.’

One of the risks posed by this reform is the popular election of judges and justices, which could enable special interest groups to influence justice in Mexico. This aspect also contradicts the USMCA in areas of trade integration (chapters 2, 18, 21, and 22) and labor (chapter 23). An atmosphere of uncertainty drives away investments that would otherwise foster economic growth and generate quality jobs.

A weak rule of law and lower legal certainty impact investor confidence in the country. According to a survey conducted by Banxico, 72% of respondents believe that the business climate will worsen over the next six months, despite the expected continuity between President López Obrador’s administration and that of President-elect Sheinbaum. This negative perception is attributed to institutional changes like the judicial reform, the reform of Pemex and CFE as state-owned enterprises, and the possible dissolution of autonomous agencies such as COFECE, IFT, and INAI (for their initials in Spanish).

The World Justice Project (WJP) recently released the Rule of Law Index 2024, which assesses perceptions and experiences of the rule of law in 142 countries. In this edition, Mexico ranked 118th out of 142. Historically, Mexico’s score has declined year after year, with actions such as the recent judicial reform contributing to this downward trend. Among the eight factors considered in the index, the lowest scores for Mexico were in “Absence of Corruption” and “Criminal Justice”.

The independence of the judiciary

In a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the concept of the ‘Executive aggrandizement’ by scholar Nancy Bermeo is revisited as a way to understand democratic backsliding in a country. For Mexico, the report analyzes four dimensions of democratic backsliding, including executive influence over the judiciary, along with indicators to assess whether former president AMLO exhibited this behavior. In the judicial dimension, AMLO displayed all of these behaviors, including the ‘use of executive decrees to limit judicial oversight of the Presidency.’

The international perception of a weakening or regression of our democracy could have serious consequences for investments and our trade relationships in North America. Institutional changes are not necessarily negative nor prohibited by the USMCA, as long as the implications do not undermine legal certainty or fair business competition.

Migration and security

Regional integration goes beyond economic indicators, and one of the ongoing challenges in foreign policy is migration, which holds opposing perspectives on both sides of the border. Similarly, in U.S. presidential debates, Mexico has often been referenced in terms of insecurity, organized crime, and corruption, which are also significant domestic and foreign policy challenges for Mexico.

In terms of migration, the elimination of trust funds supporting shelters, the use of the National Guard to detain migrants, and the reduction of the budget for the National Institute of Migration (INM) have culminated in tragic episodes. Notably, the INM has consistently exceeded its budget allocation, spending up to twice the approved amount, mainly on external services (chapter 3000). The next administration must ensure that resources allocated to the INM are used efficiently, guaranteeing human rights protections, better conditions, and efficient processing for migrants in our country.

Organized crime, fentanyl, and violence have been deemed national security issues for the U.S., impacting the perception of investors considering settling in our country and deterring regions or states labeled as high-risk. The Social Progress Index (SPI) component of Personal Safety illustrates that the security issue is not uniform across Mexico.

One example is the rate of homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. According to the latest data from Mexico Evalúa, 7 out of 32 states have a homicide rate above the national average and are on an upward trend. Among these, three are border states, bringing the issue closer to the U.S. and potentially increasing pressure to enhance migratory security.

The organized crime index variable within the SPI also reflects regional complexities across Mexico. While this index remains low in states like Tlaxcala, Chiapas, and Yucatán, it is high and rising in Nuevo León, Zacatecas, and Colima. In the U.S., organized crime is directly linked to drug trafficking, which means Mexico will need to take steps to prevent U.S. intervention that could lead to sovereignty conflicts.

Mexico facing China

The three North American economies have different trade allies and are linked to various agreements; however, the USMCA has created a significant trade dependency, especially between Mexico and the U.S.

- Mexico is the United States’ top trading partner and Canada’s second.

- 84% of Mexico’s non-oil goods exports go to the United States.

- 80% of Mexican light vehicle exports are destined for the United States and Canada.

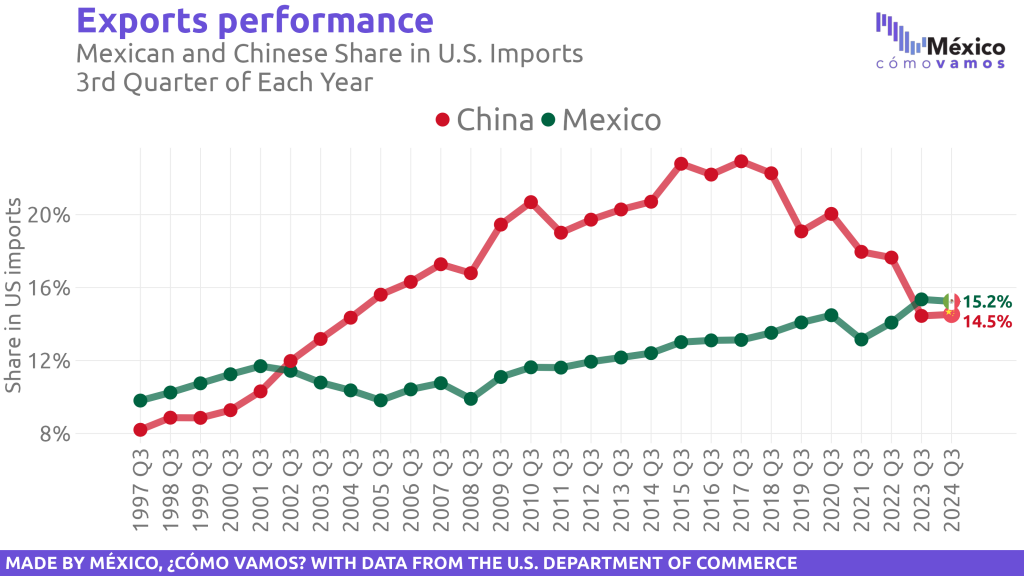

Our main trading partner is the world’s largest economy, meaning its trade policy decisions have a major impact on the region. One example is the U.S.-China trade war, given China’s significant presence in both Canada and Mexico. The topic of China has been central to U.S. presidential debates and will be critical in the 2026 review, so Mexico must start evaluating its position on China.

China’s presence in Mexico gained momentum between 1993 and 1998, doubling its share of Mexican imports. By the year 2000, it had tripled its 1993 share, and in 2009, it surpassed the European Union in the ranking of leading regions of origin for Mexican imports. Today, China stands as Mexico’s second-largest supplier, with a solid 20% of our imports, second only to the U.S.

At the same time this was happening in Mexico, the U.S. was becoming less dependent on Chinese imports. This shift began with measures implemented in 2016 to curb China’s presence in its domestic market, both in imports and investments. This led to a regionalization of trade, increasing reliance on its North American partners. Consequently, Mexico’s share in U.S. imports has grown, becoming its main trading partner.

China will be on the agenda of the next U.S. president, where protecting the country’s best interests will be the priority. But where does North America fit into that agenda?

A major task for the region will be to create an investment monitoring strategy to ensure that investors and countries respect the principles established in the USMCA.

A key consideration is that China has different bargaining power with each North American country. For example, China is a net exporter of goods but not of energy or grains, which means its dependence on countries like Canada for crops such as canola, and on the U.S. for other agricultural products, should be factored into negotiations.

- As of August 2024, Mexico has surpassed China to become the second-largest destination for U.S. agricultural exports, with Canada as the first

The necessary strategic positioning of Mexico regarding China

For Mexico, opting out of Asian investments is not an option, but the benefits of the USMCA on the economy and society have been significant, as seen in measures such as GDP per capita and FDI. Therefore, Mexico should plan a regionalization strategy that serves its best interests, protects strategic sectors that depend on China, and respects its sovereignty, aiming to maximize the benefits of its various trade relationships and alliances.

What happens if the USMCA members express a desire not to continue with the agreement in 2026?

Looking toward 2026, it is important to note that the origin of the USMCA review clause was a U.S. initiative that initially aimed to assign a short fixed term to the duration of the agreement. Following resistance from Canada and Mexico, a 16-year term was agreed upon with a review six years after its entry into force (Brookings, 2024). Thus, the purpose of the review is to allow the agreement to evolve over time and ensure that all parties are satisfied with its performance.

The USMCA is originally set to expire in 2036. The review or sunset clause in Chapter 34, Article 34.7, specifies that the Free Trade Commission (the Commission) will conduct a review of the agreement’s performance on its sixth anniversary, during which the parties may make recommendations. The parties are responsible for indicating in writing whether they wish to continue the agreement for an additional six years beyond the initially established term, meaning unilateral withdrawal by any party is always a possibility.

If all three parties agree to extend the USMCA until 2042, another review will take place in 2032, following the six-year review schedule outlined in the clause. Should consensus to continue the USMCA not be reached in 2026, the parties must conduct annual reviews until 2036, the original term set upon its entry into force. (IMCO, 2024)

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) plays a fundamental role in regional integration, so Mexico must maintain a strategy that benefits the country and improves quality of life for its people. The 2026 review will take place under new leaders in each country of the region, so aligning agendas on key opportunities and mitigating shared challenges will be the only way to ensure the continuity of the USMCA and our trade relationship.

Would you like to learn more about North American integration, the map of shared prosperity, and the integration of human capital through the USMCA?

Don’t miss out:

For more information visit mexicocomovamos.mx

Contact [email protected] and +52 55 7590 1756